Subsection 7.5.5 Statistical (Likelihood) Reasoning

Consider these two statements:

People have more neurons than earthworms do.

Healthy male birds sing faster than sick ones do.

These may sound like similar claims. But they’re different in an important way. The first is a categorical statement. All people have more neurons than all earthworms. The second, though, is a statistical statement. We might rephrase it as:

On average, healthy male birds sing faster than sick ones do.

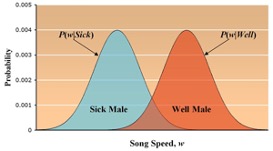

Or we could actually show the distributions for song speed for two groups of birds:

As the distribution makes clear, it isn’t true that all healthy birds sing faster than all unhealthy ones. But the statistical claim that healthy birds are faster singers than sick ones is correct.

Many everyday claims are statistical ones.

[4] Older children are taller than younger ones. (As in the bird song example, this is a claim about distributions. There certainly are 8-year olds who are taller than some 10-year olds.)

[5] In Florida, it rains in the afternoon. (This sentence means that the probability of rain in any given afternoon is very high, although not certain.)

[6] Children like ice cream better than broccoli. (Again, I won’t accuse you of lying just because I find a single child who likes broccoli better. This is a statistical claim.)

[7] It’s likely to rain tomorrow. (Sometimes we even make explicit the statistical nature of our claim.)

Fortunately, the science of statistics gives us precise tools for reasoning with these kinds of statements when we need to. And that science rests on the core logical structures that we will study. Logic is not irrelevant to this kind of reasoning. It’s just not enough.