Photo Credit: Rachel Tyler | Daily Texan Staff

Source: The Daily Texan

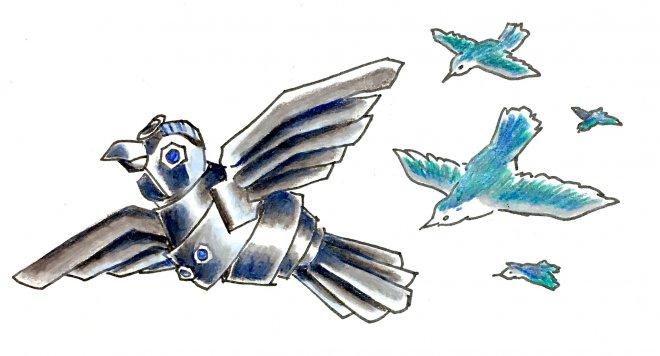

The computer simulations of artificial intelligence researcher Katie Genter could help robot birds lead real flocks away from dangerous situations.

Genter, who presented her Ph.D. dissertation on flocking behavior and other research in UT’s Learning Agents Research Group to a panel of computer scientists this May, wanted to know if she could control the movement of virtual flocks by adding certain autonomous agents into the mix.

In computer science, an agent is a computer program that acts on its own by following a series of pre-written rules. In this case, Genter developed “flocking” agents, which acted in the way a normal bird would, and “influencing” agents, which learned from the flock to push all the flocking agents in a certain direction.

“Once you know who the neighbors of a bird are, (you can determine) what behaviors of the neighbors affect the behaviors of the agent,” Genter said. “The model averages the orientation of the neighbors, and that determines the orientation of the individual agents.”

Genter said she doesn’t control these agents: They must observe neighbors to make their own decisions through a type of artificial intelligence called ad hoc learning.

“You’re joining a team that you haven’t pre-coordinated with and that you might not be able to communicate with, and you’re still helping them accomplish the goal,” Genter said.

Through her thesis and a series of papers published through computer science journals and conferences, Genter tested how different combinations of neighbors and environmental factors affected the agents.

“Intuitively I thought that the birds that were closer to the agent would have a stronger impact,” Genter said. “But … inherently there’s no reason that closer agents should have more knowledge than further agents.”

Peter Stone, director of the research group and Genter’s Ph.D. advisor, said researchers normally approach flocks by studying where they end up rather than how they can be pushed in one direction or another.

“Everybody up to this point had thought of flocking as something where all of the birds or fish are doing the same thing, rather than having this separation of flocking agents and influencing agents,” Stone said. “But we can insert some birds ourselves and influence what the rest of the flock is going to do.”

Genter said that these models have applications in real-life situations: Robot birds programmed with similar algorithms could infiltrate real flocks of birds and lead them away from dangerous areas such as airports and wind farms.

“If you design a robot bird that has the same silhouette and the same wing-flap pattern, (birds will) actually think the robot bird is just another member of the flock,” Genter said. “Our method would … not scare the birds, not kill them, not take away their natural habitat, but just … lead the flock safely around the airport.”

Dutch company Clear Flight Solutions has already developed working robot falcons and eagles, with prototypes operating at the Edmonton International Airport, but Genter said that these robots must be controlled by a human operator and rely on scaring birds away rather than leading them in a specific direction.

A representative from the city of Austin Aviation Department said in an email that the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport currently uses habitat management, spikes in roosting areas and propane cannons to keep birds away and scare them when necessary.

“Bird challenges vary by time of year,” they wrote. “(The airport is) currently rated as moderate.”

According to the Federal Aviation Administration’s wildlife strike database, the airport reported 35 strikes in 2016, with 289 strikes reported across Texas.

Genter added that the models could also be applied to insects, fish and even herds of grazing animals. Stone said that artificial intelligence could lead flocks towards areas as well as away from them.

“The airport is a representation of something that you want the flock to avoid, but in principle you could have them try to go somewhere, not avoid something,” Stone said. “You could have them try to go to wildlife preserves or avoid … areas where there’s not a lot of food for them.”

Genter, who moved to Florida after her dissertation defense, said that although she plans to tour universities around the world as a guest lecturer, there are still many questions left open by her research.

“(Researchers) could actually be able to take flocking models that biologists are proposing, try them out in our simulators and see if the resulting behavior is the same as what they’re experiencing in nature,” Genter said. “If it’s not, there’s something wrong with the model that they’re using — if it is, it validates their model.”