Photograph courtesy of JT Genter.

By Rachel Cooper, The Alcalde

For the past month, the world has been watching national soccer teams from across the globe compete in a surprising and nail-biting World Cup. Although the U.S. didn’t make the cut for the 2018 version of the quadrennial tournament, there’s an unorthodox soccer team close to home that did pretty well on the international stage—a group of Longhorns and their goal-scoring robots.

In Montreal from June 18-22, UT’s robot soccer team, UT Austin Villa, competed in the 22nd annual RoboCup competition, which began with a goal of developing a robot soccer team capable to beat the human World Cup champions by 2050. UT has competed in the annual competition since 2003, using computer science to code robots and running thousands of computer simulations in the hope of one day achieving this goal.

Computer science professor Peter Stone has been involved with RoboCup since its founding in the mid ’90s, and is now president-elect of the International RoboCup Federation. Stone formed UT Austin Villa (a play on the English soccer team Aston Villa) when he arrived at UT and has been the leader of the team of mostly graduate and PhD students ever since. Stone says while the organization’s goal of competing robots with humans might be a dated idea, he still hopes to see it achieved one day.

“It’s very ambitious and we’re not close to it yet, but there’s still 30 more years and things change very rapidly technologically in our day and age,” Stone says. “I wouldn’t bet too much on it happening, but I also wouldn’t bet too heavily against it.”

The original event that began in 1997 focused on robots in soccer, and has now expanded to more than 10 different leagues, with competitions outside of soccer. Currently, UT competes in the Standard Platform League, the 3-D Simulation League, and RoboCup@Home that focuses on robot service capabilities in the domestic realm. Even with the growth of RoboCup, Stone says soccer remains the focal point.

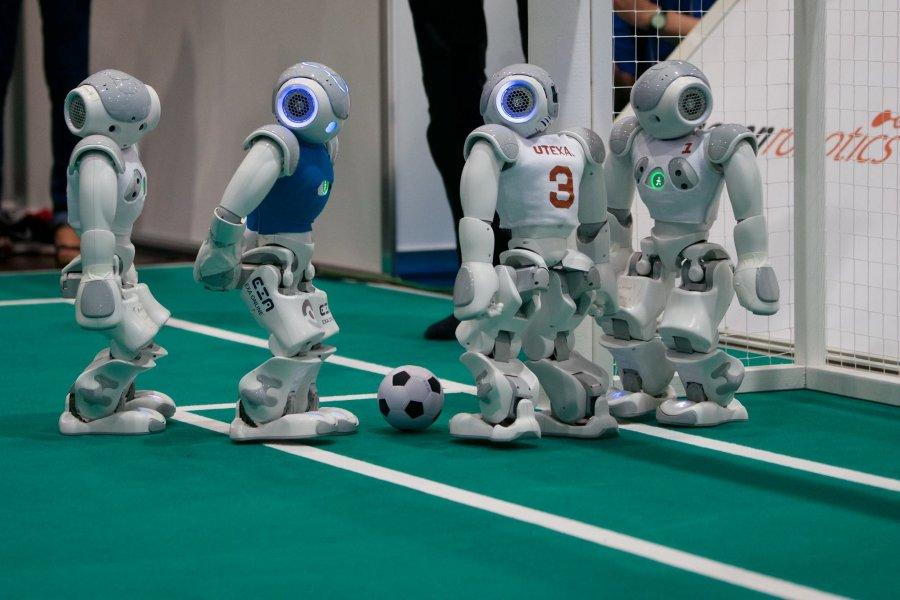

The league closest to standard soccer that UT competes in is the Standard Platform League, which uses roughly 12-pound, 2-foot-tall humanoid NAO robots to play a five-on-five game of soccer. The robots shuffle slowly around a miniature field, kicking the ball and falling over regularly. UT became champions in this league in 2012, and this year, the team was knocked out right before the semifinals, finishing in the top eight.

This was the ninth year of competition for team member Katie Genter, PhD ’17, who was drawn to UT partly because of the university’s involvement in RoboCup. Genter is part of the executive committee for the Standard Platform League, where she helps develop the league and introduce more complex aspects of the game in preparation for real play, some of which seem ambitious with the league’s current state of slow and fumbling movements.

“This year we put free kicks into the games, but next year we may put corner kicks, or throw-ins, or maybe try to get the league toward having passing,” she says. “There’s very few teams that do passing right now, but that’s obviously something that’s going to need to come in to gameplay as we move to bigger fields and to playing more intelligent opponents.”

Recently, UT has been successful in the 3-D Simulation League, where coded humanoid robots play a simulated, yet physically realistic, virtual match. The team has won the competition seven out of the last eight years, which Patrick MacAlpine, PhD ‘17, a post-doctoral fellow who has been leading the team since 2010, says is largely due to machine learning. This aspect allows the computer to learn new behaviors for the simulated robots—simple actions such as walking, kicking a ball, and even getting up from a fall have proven a crucial advantage for the team.

“Now that we’ve developed the basic abilities, we’re at the point where we can start thinking more about strategy and coordination among the robots,” MacAlpine says. “I’d like to start applying more machine learning, not just to the low-level skills for our robots, but actually high-level strategy. That’s something we really started to do this past year.”

RoboCup is held every year, giving teams frequent chances to keep improving and competing. However, MacAlpine says the years the competition coincides with the World Cup are more exciting—this year the competition took place during the group stage of the World Cup, and MacAlpine recalls the fun in being able to watch matches with natives from different countries. The international community created in both tournaments is a centerpiece of the competitions, as teams from all over the world bring in different perspectives and strategies to the same game. UT is one of just a handful of U.S. teams represented at RoboCup, and Genter says being able to compete internationally is one of the best aspects.

“I love getting to meet and create pretty lasting relationships with a lot of the other teams,” Genter says. “You see them once or twice a year, but you’re all working toward the same problem. You have people that are doing their PhDs in Germany, Iran, Chile, and all over the world, and you’re coming together for this one goal.”